Sittin’ On the Docket At VA

And now for something completely different.

This is a blog post about designing algorithms for government. “Algorithm,” in this context, just means “an automated way of making a decision.” I am going to describe, in great detail, a specific algorithm that I created for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). If you’re a U.S. Veteran who had an active case with the Board of Veterans Appeals (the Board) at any time since November 2018, this algorithm affected your appeal.

This post is going to get wonky. And it’s very long. I’m going to try my best to inverted pyramid this thing. It’s entirely okay to stop reading when you’ve had enough. There isn’t a twist at the end. There isn’t a reward for having finished it. The only reward is more detail. There is no bottom.

I’m sorry.

Why does any of this matter?

I hope to illustrate three things.

First, this is a story about automation. In this story, I automate a manual, bureaucratic process, from start to finish. But no one was fired, and in fact, the people who used to own the process were thrilled to be able to focus on more important work. To quote Paul Tagliamonte, “Let machines do what machines are good at, let humans do what humans are good at.” Everyone on all sides of this automation story was committed to doing right by Veterans. I sought to approach the task with the same level of care as its former stewards had done for many years, and I leveraged insights from the manual steps they had worked out through trial and error.

Automating this process involved more than just translating legal rules into instructions for a machine. The manual process involved bounded but significant discretion to ensure that the appeals continued to move apace. As we’ll see, a statutory change created even more opportunities for discretion. Machines don’t do discretion (or at least, they shouldn’t). So in concretizing the process into an algorithm, that discretion falls to the algorithm’s designer. Automation is thus a kind of rulemaking, but without established methods of public participation like notice-and-comment. And even while the decision space was sufficiently constrained to preclude bias on the basis of protected factors, I still needed to grapple with fundamental questions of fairness and ensure that humans remained in the driver’s seat.

Second, this is a story about complexity. You hear about civil servants studiously attending to their small niche of bureaucratic arcana, and this is a guided tour of one such niche. It’s not my niche; I was just a visitor. If, a couple thousand words into this post, the fleeting thought “maybe this whole process should just be simpler” crosses your mind, I understand. And maybe it should be! Sometimes complexity is a once good idea that’s gone rotten with time. Sometimes it was always a bad idea. But I guarantee there was intention behind the complexity. It’s trying to help someone who was left behind. It’s there because a court ordered that it must be, or because Congress passed a law. And sometimes, it might actually be load-bearing complexity. Take a sledgehammer to it at your own risk.

I think we should strive to “make it simpler” more often. Certainly I feel that Congress and the courts rarely give the challenges of implementing their will due consideration, nor do they always consider how things like administrative burden can adversely affect outcomes. But from the standpoint of most government workers, you have no choice but to make complexity work every single day. This is a story about how to make it work.

Finally, this is a story about transparency. The system that we are going to be looking at was developed in the open. Anyone in the world could check out its source code or read discussions the team had while designing and building it. This system manages every Veteran’s appeal, and instead of asking them to trust us, we’re showing our work. Because the U.S. government built it, it’s in the public domain, and you can find it on GitHub.

Except that’s a dead link. It’s dead because VA decided to take a project that had successfully operated with complete transparency for more than three years and hide it from the public. I don’t know why they decided to do that; I was long gone. I have no reason to believe there were any nefarious motivations, apart from a desire of certain officials to steer the project in a very different direction than that which my team believed in (a direction that, as the subsequent years have made clear, has not worked out).

So I’m going to have to describe the algorithm as it existed when I left VA in May 2019. I can tell from the Board’s public reports that, at a minimum, the parameters of the algorithm are set to different values than when I left (which is great; that’s why I put them there). Maybe the algorithm itself has been completely replaced (that would be cool; I don’t have a monopoly on how to solve the problem, and maybe I got something wrong!).

What’s not cool is that the public has no way of knowing, that Veterans have no way of knowing. For all I know, the algorithm has been replaced by an octopus (literal or figurative).

It is just a tiny component of a tiny system in a tiny part of VA, which is just one part of the U.S. federal government. But all across government, more and more decisions are being automated every day. For all the attention paid to the introduction of automation into decisions of enormous consequence rife with potential for discrimination (rightly so!), there are a host of smaller decisions that nevertheless matter to someone. How we approach the task of automating these decisions matters. The guardrails we put around it matter. Whether anyone even understands how the decision was made matters.

If you make it to the end of this post (and again, it’s really, really okay if you don’t), you will be able to explain every decision this particular algorithm will ever make. Why shouldn’t every government algorithm be knowable in this way? No, you couldn’t possibly invest the time to understand each and every algorithm that affects your life (are you absolutely sure you want to invest it here?), but wouldn’t it be reassuring to know that you theoretically could? (And, satisfied in the knowledge that you could have read this post to the end, wouldn’t it be so much better to go to your local library and pick up a nice Agatha Christie?)

What it do?

When a Veteran appeals a decision made by VA, such as a denial of a claim for disability benefits, they enter a sometimes years-long, labyrinthine process. Eventually, their case will reach the Board, a group of more than 130 Veterans Law Judges and their teams of attorneys, who decide the appeal.

At time of writing, there are more than 200,000 appeals waiting for a decision from the Board.[1] These appeals wait on a “docket,” which is lawyer speak meaning they wait in a line. Per the regulations, “Except as otherwise provided, each appeal will be decided in the order in which it is entered on the docket to which it is assigned.”[2]

When a judge is ready to decide another appeal, they need to retrieve the first case on the docket, the next case in line. The algorithm we’re discussing determines what case to give the judge. It’s called the Automatic Case Distribution algorithm.

That’s it. Really. “What’s the next case in line?” is all we’re doing here.

Of course, as you scroll through this 6,400 word blog post, you can probably guess that it’s going to get a lot more complicated than your average deli counter. The manual process was run by a team of four people (with other responsibilities too), armed with lots and lots of Excel spreadsheets.

Then Congress passed the Veterans Appeals Improvement and Modernization Act of 2017. Now the Board would have not one, but four dockets. Any chance that four humans could keep track of it all went out the window. Now automation wasn’t optional, it was essential. But before tackling all of that complexity, I started by automating just the one docket. So let’s start there too.

Easy mode: a single docket

When an appeal arrives at the Board, it is assigned a sequential docket number that starts with the date.[3] If we just sort the appeals by that number (and thus, implicitly, by the date they arrived), we’ll get a list of appeals in docket order.

Judges request appeals in batches, which they’ll divvy up among their team of attorneys, who will review the available evidence and write decisions for the judge to review and sign.

In order to supply a judge with a fresh batch of cases, the team managing the docket would run a report in the legacy Veterans Appeals Control and Locator System (VACOLS) to retrieve a spreadsheet of the oldest cases ready to be decided. Working in docket order, they would move the requested number of cases to the judge in VACOLS and email the judge a list of those cases for tracking. (Before the case files were digitized, the paper case file would also need to be sent to the judge’s office.)

It’s pretty easy to imagine what this process looked like once automated. The judge would log into Caseflow, the system we were building to replace VACOLS. Assuming they had already assigned all of their pending cases to attorneys, they would be presented with a button to request a new batch of appeals. Click that and new cases would appear, ready to be assigned.

One downside of the automated approach relative to the manual process was that I designed it to always assign each judge a set number of cases, three cases for each active attorney on the judge’s team. This parameter, cases per attorney, was configurable by the Board, but not by individual judges. Back when the humans were running things, judges were able to request whatever number of cases they wanted. But in user research with judges, we didn’t hear that anyone really needed to customize the number of cases, a finding that was confirmed after we launched and didn’t get any pushback. Using a fixed number of cases, called the batch size, kept things more predictable.

There are two complications we have to care about. First, some cases are prioritized. A case can be prioritized because it is Advanced on the Docket (AOD), a status granted to cases where the Veteran is facing a financial or other hardship, a serious illness, or is 75 years or older. A case can also be prioritized because the Board’s decision was appealed to the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims (CAVC) and it was remanded back to the board to correct a problem. If the case is prioritized, it must be worked irrespective of docket order.

Second, if a judge had held a hearing with the Veteran, or if they had already issued a decision on the appeal, that appeal is tied to the judge and must be assigned to them, and no one else. If the judge retires, the Veteran would need to be offered another hearing with a different judge before the Board could decide the case.

For these reasons, the humans had a more difficult task than just selecting the first several rows of a spreadsheet. Prioritized cases were front of the line, but they didn’t want any single judge to become a bottleneck after getting assigned too many of the most time-sensitive cases, so the team would try to ensure that each judge got a balanced number of AOD cases, while also ensuring that no AOD case sat too long.

If there were cases that were tied to a particular judge, it wouldn’t make sense to assign that judge a bunch of cases that could have been worked by anybody (gen pop cases). So the team was allowed look past the strictly oldest cases on the docket to keep things moving. In order to keep this aboveboard (after all, cases are supposed to be assigned in docket order), each week the team would determine a “docket month” by calculating the age of the Nth oldest case, where N was a number that was agreed upon by the Board and stakeholders. Any case that was docketed in that month or before was considered fair game, giving the team the wiggle room they needed to keep things moving smoothly.

The algorithm basically replicates this approach, with some machine-like flair. The concept of docket month, an easy-to-use tool for humans to keep track of which cases they could assign, is an unnecessary abstraction for a computer. I replaced it with a concept called docket margin. Even though judges request cases on their own schedules, the algorithm starts by asking, “What if every single judge requested a new batch of cases at the same time? How many cases would I distribute?” That count is our docket margin, a rough estimate of the concurrent bandwidth of the Board.

To determine how many prioritized cases to give to each judge, we count the number of prioritized cases and divide it by the docket margin to arrive at the priority target. Multiplying the batch size by this proportion and always rounding up, we arrive at the target number of prioritized appeals we want to distribute to the judge.

Here’s some Ruby code. The code is just another way of saying the same thing as the above paragraph, so if don’t like to read code, you’re not missing anything.

def priority_target

proportion = [legacy_priority_count.to_f / docket_margin, 1.0].min

(proportion * batch_size).ceil

endWe can also use the docket margin to derive the docket margin net of priority, which is the docket margin minus the count of prioritized cases. Like the docket month, this range determines how far back we are allowed to look on the docket and still be considered to be pulling from the front of the line. Unlike the docket month, it is calculated on demand and is more precise.

def docket_margin_net_of_priority

[docket_margin - legacy_priority_count, 0].max

endNow we have everything we need to distribute cases from our single docket. The algorithm has four steps.

In the first step, we distribute any prioritized appeals that are tied to the judge requesting cases. As no other judge can decide them, we will distribute as many such appeals as we have ready, up to the batch size.

In the second step, we distribute any non-prioritized appeals that are tied to the judge. We will again distribute an unlimited number of such appeals, but only searching within the docket margin net of priority, i.e. the cases that are considered to be at the front of the line.

Note that, in terms of the ordering of the steps, we are considering first whether the appeal is tied to a specific judge before considering whether the appeal is prioritized. This is because at the micro level, it’s more important for any given judge to be working the cases that only they can work. At the macro level, between the Board’s more than 130 judges, there will always be plenty of judges available to work AOD cases quickly. Note that even in extreme circumstances, such as if every appeal was tied to a judge, the algorithm would be self-healing, because the docket margin net of priority shrinks the more prioritized cases are waiting, thus reducing the number of cases distributed in step two.

In the third step, we check the priority target. It’s possible we already hit or even exceeded the target in step one, in which case we skip this step. But if we still need more prioritized cases, we’ll distribute gen pop prioritized cases until we reach the target. In order to ensure that prioritized cases continuously cycle, they are not sorted by docket date, but rather by how long they’ve been waiting for a decision, or in programmer speak, a first-in, first-out (FIFO) queue.

At any point, if we have reached the limit of the batch size, we stop distributing cases. Our work is done.

But assuming we still need more cases, our fourth and final step is to look to non-prioritized, gen pop appeals. We distribute those in docket order, until the we’ve reached the batch size and the judge has the cases they need.

Here’s what it looks like in code:

def legacy_distribution

rem = batch_size

priority_hearing_appeals =

docket.distribute_priority_appeals(self,

genpop: "not_genpop",

limit: rem)

rem -= priority_hearing_appeals.count

nonpriority_hearing_appeals =

docket.distribute_nonpriority_appeals(self,

genpop: "not_genpop",

range: docket_margin_net_of_priority,

limit: rem)

rem -= nonpriority_hearing_appeals.count

if priority_hearing_appeals.count < priority_target

priority_rem =

[priority_target - priority_hearing_appeals.count, rem].min

priority_nonhearing_appeals =

docket.distribute_priority_appeals(self,

genpop: "only_genpop",

limit: priority_rem)

rem -= priority_nonhearing_appeals.count

end

nonpriority_appeals =

docket.distribute_nonpriority_appeals(self,

limit: rem)

[

*priority_hearing_appeals,

*nonpriority_hearing_appeals,

*priority_nonhearing_appeals,

*nonpriority_appeals

]

endCongratulations, that’s one full government algorithm. It was turned on in production in November 2018, but it would only stay on for three months…

The Appeals Modernization Act

On August 23, 2017, the Veterans Appeals Improvement and Modernization Act of 2017, a.k.a the Appeals Modernization Act (AMA), was enacted into law. The first significant reform of the VA appeals process in decades, VA was given 540 days to implement the new law. There’s no possible way this already overstuffed post can accommodate my opinions about AMA and how it was implemented, so let’s just narrowly focus on what this new law meant for the Automatic Case Distribution algorithm.

My team was working to replace VACOLS—a legacy system, built in PowerBuilder, that had been maintained for decades by a single person—with Caseflow. The passage of AMA was a clarifying moment for our team. It was quickly apparent that there was no path for VACOLS to be retrofitted for the new law, so the 540-day clock provided a deadline for Caseflow to be able to stand on its own two legs.

545 days later, VA was ready and the law went into effect. Nothing changed for Caseflow. Every single piece of new functionality had already gone live in production and been used to manage the real appeals of real Veterans via the Board Early Applicability of Appeals Modernization (BEAAM) program,[4] which invited a small group of 35 Veterans to conduct a trial run of AMA. The program not only helped to ensure a smooth rollout of the technology, but it also gave us valuable insights as we prepared updated regulations and procedures for the new law and designed informational material for Veterans and their representatives.

By the way, I think this is the Platonic ideal of government IT launches. You just throw a nice party for the team because everything has already shipped.

Everything had gone live, that is, except for the new version of the Automatic Case Distribution algorithm. The whole reason we implemented the single-docket algorithm described above, despite only needing it for three more months, was so that we could roll out as much as possible ahead of the applicability date of the law. But on AMA day, we had to flip a feature flag and swap in a completely different algorithm.

In order to test the new algorithm ahead of time, I built a discrete-event simulation (DES) to model what the Board would look like under AMA, and I used that to pressure test the algorithm under various conditions. I had done the same for the single-docket version before rolling it out too, although that was easier thanks to decades of historical data. For example, when I said above that docket margin net of priority was “more precise” than docket month, the evidence for that claim before we took the algorithm live was simulation results showing that it never had to look more than 3,000 cases deep on the docket, which was narrower than the range the humans were using at the time. I evaluated various algorithms using four measures: (1) docket efficiency, how deep the algorithm had to look on the docket to find cases; (2) distribution diversity, how balanced prioritized cases were between judges; (3) priority timeliness, how long it took to distribute a new prioritized case; and (4) priority pending, the maximum number of prioritized cases waiting at any given time.

The challenge was that for AMA, I was modeling a novel and highly complex procedural framework with only limited data as to what might happen (collecting a preliminary evidence base was another goal of the BEAAM program, which featured extensive interviews with Veterans and their representatives to explore how they would approach making choices under AMA). It was extremely important to test the algorithm under extreme scenarios, not just how VA hoped they would play out.

AMA says, “The Board shall maintain at least two separate dockets,”[5] one for appeals that requested a hearing, and one for appeals that didn’t. The Board chose to create not two, but three dockets. As required by the statute, one docket would be for appeals that requested a hearing. A second docket would be for appeals that didn’t request a hearing, but where the Veteran had added new evidence to their case that had not been reviewed by the agency that had originally made the contested decision (i.e. the Veterans Benefits Administration for disability benefit claims). A final docket, the “Direct Review” docket, would offer Veterans the guarantee of a faster decision in exchange for not requesting a hearing or adding new evidence. When a Veteran appealed a decision to the Board, they would have to choose which docket they wanted to use. And as the dockets were maintained separately, the Board could choose how to allocate resources between them, working some dockets faster than others, while still respecting docket order within any given docket.

Veterans who already had an appeal could keep it under the old “legacy” rules. As a result, there would now be four separate dockets for the algorithm to consider: the hearings docket, the new evidence docket, the Direct Review docket, and the legacy docket.

The Board’s policy goals

The Board articulated three policy goals to inform the design of the algorithm. As is often the case, the goals are sometimes vague and contradictory. That’s what makes this fun, I guess.

The first goal was not vague. Appeals on the Direct Review docket should be decided within one year, 365 days. I understood at the time that this was not realistic in the medium term,[6] but the Board was unwilling to acknowledge that fact. As of December 2024, appeals on the Direct Review docket take an average of 722 days to complete, down from a peak of 1,049 days in July 2024.[7] Absent any staffing reductions, it is possible that the Board will be able to reach a steady state where it consistently achieves its goal by 2026. From the perspective of algorithm design, I sought to give the Board the best shot at achieving its goal, while also ensuring the Board didn’t shoot itself in the foot if the goal turned out to be unachievable.

The second goal was that the dockets should be balanced “proportionately.” The definition of “proportionately” was left to me to interpret, but any definition was in contradiction with the other two goals. In the end, I excepted the Direct Review docket from any claim of proportionality and rearticulated this goal as “the other dockets should be balanced proportionately.”

The third goal was that the Board would prioritize completing legacy cases. The size of the legacy appeals backlog, then about 400,000 cases, was the primary reason I felt the first goal was not realistic. Under the legacy rules, Veterans have options to keep an appeal going almost indefinitely, so the Board will continue to work legacy appeals for literal decades. However, unless the Board clung too long to the 365-day goal for the Direct Review docket, I expected the Board could reach “functional zero” by 2025 or 2026, where only a small proportion of its resources were going toward the long tail of legacy appeals.

Keeping these goals in mind, let’s take a look at the AMA algorithm. Or, you know, maybe you could take a pleasant walk in the fresh air instead?

Hard mode: four dockets

As before, we start by calculating the docket margin and docket margin net of priority, only now looking at prioritized cases on any of the four dockets.

Setting aside the prioritized cases for a moment, we need to determine what proportion of non-prioritized cases should come from each of the dockets. Each docket has a weight, which is generally equal to the number of non-prioritized cases waiting.

The legacy docket’s weight is adjusted to account for cases that we know about, because the Veteran has filed a Notice of Disagreement, but which have yet to come to the Board and be docketed, because they are waiting on a Form 9. About 40% of Notices of Disagreement end up reaching the Form 9 stage, so we add a discounted count of pre-Form 9 cases to the number of docketed cases to give us the legacy docket’s weight.

class LegacyDocket

# When counting the total number of appeals on the legacy docket for purposes of docket balancing, we

# include NOD-stage appeals at a discount reflecting the likelihood that they will advance to a Form 9.

NOD_ADJUSTMENT = 0.4

def weight

count(priority: false) + nod_count * NOD_ADJUSTMENT

end

# ...

endWe’ve now fulfilled the Board’s second goal, and calculated a set of proportions using the size of each docket. If that was our only goal, we could stop, but in response to the other two goals, we’ll make need to make two adjustments.

First, we need to fix the Direct Review docket such that cases are decided within 365 days. When a case is docketed on the Direct Review docket, Caseflow stamps it with a target decision date, 365 days after the day it was docketed. We record the target decision date for each case to enable the Board to later adjust the timeliness goal (should it prove to be infeasible), while continuing to honor the commitment that was made to Veterans when they chose the Direct Review docket. The goal is adjusted for future cases, but we continue working the cases we have within the time we promised.

From the target decision date, we can derive the distribution due date, the date that we want to start looking for a judge in order to get a decision out the door by the 365 day mark. This was initially 45 days before the target decision date, but we planned to adjust this number as we got real-world data.

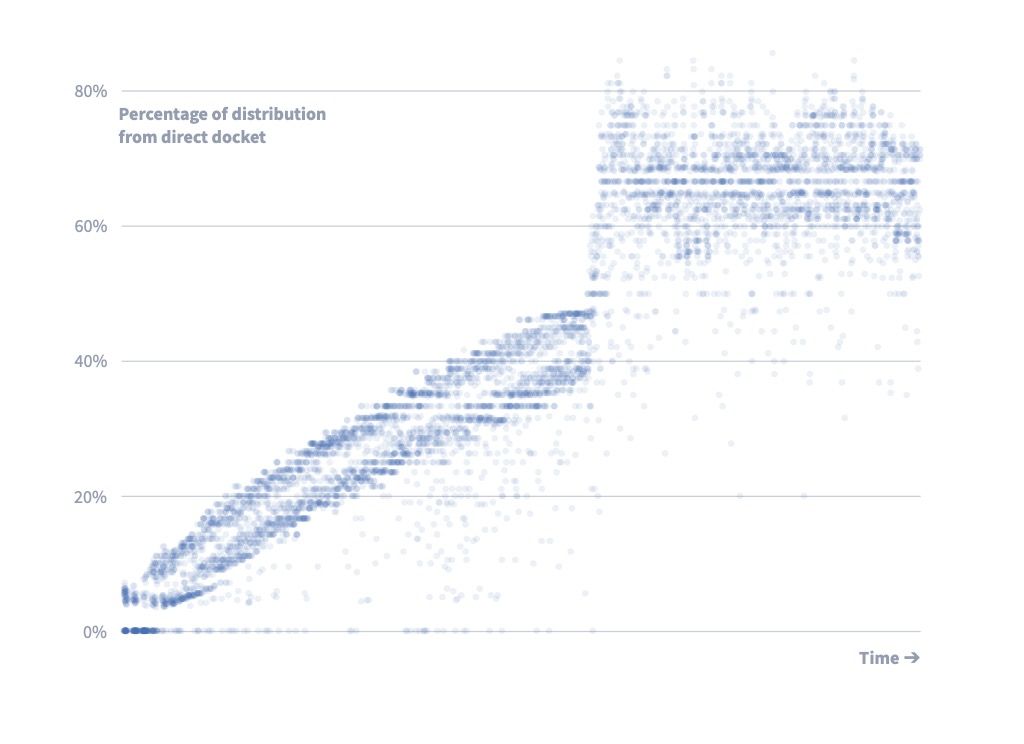

We can count the number of cases where distribution has come due and divide by the docket margin net of priority to calculate the approximate proportion of non-prioritized cases that need to go to Direct Reviews in order to achieve the timeliness goal. Initially, no cases are due, and so this proportion would be zero. But the Board didn’t want to wait to start working Direct Review appeals, preferring to start working them early and notch the win of beating its timeliness goal (even if this wasn’t sustainable). As a result, I constructed a curve out for the Direct Review docket.

We start by estimating the number of Direct Reviews that we expect to be requested in a year. If we’re still within the first year of AMA, we extrapolate from the data we have. We can divide this number by the number of non-priority decisions the Board writes in a year to calculate the pacesetting Direct Review proportion, the percentage of non-priority decision capacity that would need to go to Direct Reviews in order to keep pace with what is arriving.

def pacesetting_direct_review_proportion

return @pacesetting_direct_review_proportion if @pacesetting_direct_review_proportion

receipts_per_year = dockets[:direct_review].nonpriority_receipts_per_year

@pacesetting_direct_review_proportion = receipts_per_year.to_f / nonpriority_decisions_per_year

endOur goal is to curve out to the pacesetting proportion over time. So we calculate the interpolated minimum Direct Review proportion, using the age of the oldest waiting Direct Review appeal relative to the current timeliness goal as an interpolation factor. We apply an adjustment to this proportion, initially 67%, to lower the number of cases that are being worked ahead of schedule.

def interpolated_minimum_direct_review_proportion

return @interpolated_minimum_direct_review_proportion if @interpolated_minimum_direct_review_proportion

interpolator = 1 - (dockets[:direct_review].time_until_due_of_oldest_appeal.to_f /

dockets[:direct_review].time_until_due_of_new_appeal)

@interpolated_minimum_direct_review_proportion =

(pacesetting_direct_review_proportion * interpolator * INTERPOLATED_DIRECT_REVIEW_PROPORTION_ADJUSTMENT)

.clamp(0, MAXIMUM_DIRECT_REVIEW_PROPORTION)

endThis gives us a nice curve out, as shown below. The jolt upward occurs when we catch up with the distribution due date of the docketed appeals.

We also apply a limit to the number of cases that can go to the Direct Review docket, initially set at 80%.

direct_review_proportion = (direct_review_due_count.to_f / docket_margin_net_of_priority)

.clamp(interpolated_minimum_direct_review_proportion, MAXIMUM_DIRECT_REVIEW_PROPORTION)The second adjustment that we apply to the raw proportions is that we set a floor of 10% of non-priority cases to come from the legacy docket, provided there are at least that many available. This adjustment ensures that the Board continues working the legacy appeals backlog, even as it dwindles to only a handful of cases.

A brief aside

An implicit assumption here is that the Board needed to be willing to admit when it was no longer able to meet the 365-day goal. The 80% limit gave me confidence that at least nothing would break. But if the percentage of Direct Reviews was continuously pegged to 80%, there would be scarce capacity to work anything other than Direct Reviews, and in particular, to work down the legacy appeals backlog.

To this day, VA.gov reads, “If you choose Direct Review, […] the Board’s goal is to send you a decision within 365 days (1 year).” VA continued to make that promise to Veterans even as it was issuing decisions on Direct Reviews that were more than 1,000 days old.

Again, because it’s hidden from the public, I don’t know how the Board has updated the algorithm’s parameters, or even if they’re still using it. But it’s quite apparent from publicly available data that whatever algorithm is in use, the Board has not been able to keep pace with the 365-day goal it continues to claim. Fortunately, it looks like things started to turn around in 2024 as the legacy backlog began to dry up, and it’s possible the Board will be able to meet its stated goal within the next couple years. If its staffing levels aren’t cut.

Hearings make this even harder

Okay, one last complication. Under AMA, cases on the hearings docket get distributed to judges as soon as they are ready, generally after the hearing has occurred, been transcribed, and the evidentiary period (the time after the hearing in which the Veteran can add new evidence to their case) has expired or been waived. The Board’s term for this is “one-touch hearings,” which is in contrast to legacy hearings, which could take place months or even years before the case was decided. As a result, the number of cases that get worked on the docket is not decided when cases are distributed, but rather when we determine how many AMA hearings to hold.

Fortunately, Caseflow is also responsible for scheduling hearings. Every quarter, Caseflow Hearing Schedule asks Caseflow Queue (where the algorithm lives) to tell it the number of AMA hearings it should schedule. Caseflow calculates the docket proportions, as above, and multiplies the hearings docket proportion by the number of non-prioritized decisions it plans to issue that quarter.

def target_number_of_ama_hearings(time_period)

decisions_in_days = time_period.to_f / 1.year.to_f * nonpriority_decisions_per_year

(decisions_in_days * docket_proportions[:hearing]).round

endOne complication of this number is that a Veteran could withdraw their hearing request. Due to a legal technicality, however, their appeal would remain on the hearings docket. This means that Caseflow Hearing Schedule needs to look to whether the hearing request had been withdrawn. If so, it marks the case as ready for a decision; if not, it schedules a hearing.

Under AMA, cases with hearings are not required to be decided by the same judge who had held the hearing, as they were under the legacy rules. However, it remains better for everyone involved if the same judge decides the case, if possible, so the algorithm continues to mostly work the same, which I termed affinity. The only difference between affinity and the old rules is that if a judge retires or takes a leave of absence, Caseflow treats the cases they heard as gen pop, available to be assigned to anyone, instead of requiring another hearing.

At long last, let’s automatically distribute some cases

Okay, so now we know the proportion of the Board’s decisions that should be allocated to each docket. We’ve helped Caseflow Hearing Schedule hold the right number of hearings some months ago. Now a judge comes along and asks for a new batch of cases. Let’s help them out, shall we?

As before, we calculate the priority target and docket margin net of priority. The only difference is that we now need to look at the number of prioritized appeals on any of the four dockets. We’ll also calculate how deep we can look on the legacy docket specifically, the legacy docket range by multiplying the docket margin net of priority by the legacy docket proportion.

def legacy_docket_range

(docket_margin_net_of_priority * docket_proportions[:legacy]).round

endWe can start distributing appeals by looking at cases that are either tied to the judge (legacy docket) or have affinity for the judge (hearings docket). And of course, prioritized cases go first.

# Distribute priority appeals that are tied to judges (not genpop).

distribute_appeals(:legacy, limit: @rem, priority: true, genpop: "not_genpop")

distribute_appeals(:hearing, limit: @rem, priority: true, genpop: "not_genpop")

# Distribute nonpriority appeals that are tied to judges.

# Legacy docket appeals that are tied to judges are only distributed when they are within the docket range.

distribute_appeals(:legacy, limit: @rem, priority: false, genpop: "not_genpop", range: legacy_docket_range)

distribute_appeals(:hearing, limit: @rem, priority: false, genpop: "not_genpop")Next, we need to see if we’ve reached the priority target, and if not, distribute more prioritized cases. We’ll need to find prioritized cases irrespective of docket, looking at how long the case has been sitting rather than its docket order to ensure that prioritized cases keep moving. This is a two step process, where we ask the databases which dockets have the oldest appeals first and then distribute that many appeals second. As a result, there is a risk of a race condition where two judges could request cases at approximately the same time and the second judge would get a case that wasn’t strictly the oldest. Any case that is skipped over in this way would likely be picked up by the very next judge, so it wasn’t necessary to try to implement some form of locking (not trivial because legacy appeals are stored in VACOLS), but it was important to flag that edge case in our documentation so we weren’t hiding even a trivial deviation from our stated procedures.

# If we haven't yet met the priority target, distribute additional priority appeals.

priority_rem = (priority_target - @appeals.count(&:priority)).clamp(0, @rem)

oldest_priority_appeals_by_docket(priority_rem).each do |docket, n|

distribute_appeals(docket, limit: n, priority: true)

endNow we need to distribute the remaining non-prioritized cases. We’ll deduct the non-priority appeals that we’ve already distributed from the proportions, and then it’s time to figure out how many cases we distribute from each docket.

If we were to multiply the docket proportions by the number of cases we have left in the batch size, it’s quite unlikely we would get an whole number result, and it’s rather difficult to distribute a fraction of a case. To avoid this, we’ll use a form of stochastic rounding to ensure we distribute the requested number of cases and don’t leave any docket behind.

In our stochastic rounding method, we multiply the docket proportions by the number of cases remaining. We always allocate each docket any whole number of cases, but we set aside the remainders. Using these remainders as weights, we probabilistically allocate the remaining cases to dockets. While each individual batch can vary, over many distributions, the actual proportions will converge toward the target proportions, and even dockets that are wildly outnumbered will still get the right amount of attention.

# Extends a Hash where the values represent parts of a whole.

#

# {

# a: 0.5,

# b: 0.25,

# c: 0.25

# }.extend(ProportionHash)

module ProportionHash

def stochastic_allocation(num)

result = transform_values { |proportion| (num * proportion).floor }

rem = num - result.values.reduce(0, :+)

return result if rem == 0

cumulative_probabilities = inject({}) do |hash, (key, proportion)|

probability = (num * proportion).modulo(1) / rem

hash[key] = (hash.values.last || 0) + probability

hash

end

rem.times do

random = rand

pick = cumulative_probabilities.find { |_, cumprob| cumprob > random }

key = pick ? pick[0] : cumulative_probabilities.keys.last

result[key] += 1

end

result

end

# ...

endWe run this step in a loop, in case any docket runs out of available cases (quite likely with the hearings docket, where most cases have affinity for a judge). At the end of each pass, we zero out the docket proportion of any docket that has been unable to supply us with all of the cases we requested, we normalize the proportions to sum to 100%, and then we re-run the stochastic allocation method. We repeat until we’ve either provided the judge with all the cases they need, or all of our dockets run out of cases.

until @rem == 0 || @remaining_docket_proportions.all_zero?

@remaining_docket_proportions

.normalize!

.stochastic_allocation(@rem)

.each do |docket, n|

appeals = distribute_appeals(docket, limit: n, priority: false)

@remaining_docket_proportions[docket] = 0 if appeals.count < n

end

endMonitoring and tweaking

Each time a judge requests a distribution, Caseflow records the state of the world as the algorithm saw it, enabling us to reconstruct why it made the decisions it made and to study the behavior of the algorithm in the real world. All of this data was reported on an easy-to-use dashboard so that Board staff could understand whether the algorithm was still correctly configured to meet their goals and to provide an “early warning” system for when things were clearly no longer sustainable.

I took my best stab at initial values for the different parameters of the algorithm. But these things were parameterized explicitly in anticipation that they would need to change. All told, the Board could control the batch size per attorney, the Direct Review docket time goal, the Direct Review distribution due date, the maximum Direct Review proportion, the interpolated Direct Review proportion adjustment, and the minimum legacy docket proportion. The Board also had the option of overriding the recommended number of AMA hearings to schedule.

Tweaking these parameters could adapt the algorithm to any situation that I could anticipate, and hopefully many that I couldn’t. It also ensured that the decisions made by the algorithm remained properly within the control of VA leadership and were not coopted by an enigmatic machine.

Fin

Figuring all that out was maybe 10–20% of my job for four months of my life. All of the code is pretty straightforward and boring. It’s learning the whys behind the existing process, working out of what needed to change, finding ways to test it to make sure nothing went horribly wrong, getting feedback and buy-in from stakeholders, documenting and explaining it to different audiences; that’s where the real challenge was. Anyway, that’s my experience of what it looks like to actually automate bureaucracy.

I did say there isn’t a reward for making it to the end. I hope you’re happy.

VA Board of Veterans’ Appeals Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2024 ↩︎

Unfortunately, the Board used a two-digit year for this date. The Board was created in 1930, so it has its own flavor of Y2K bug scheduled to hit in 2030. Generally speaking, there shouldn’t be new appeals using this docket numbering scheme after 2019, but it’s possible for a closed appeal to be reopened through a finding of clear and unmistakable error, which would result in a new docket number being assigned. The Board still has four years to decide how to fix that one, and I built error messaging to ensure no one forgets. ↩︎

I designed and managed the program, but I’m not responsible for the name. Technically, we used the authority under section 4 of AMA (“Programs to test assumptions relied on in development of comprehensive plan for processing of legacy appeals and supporting new appeals system”), not the provisions of section 2(x)(3) (“Early applicability”), as the name inaccurately suggests. Yes, it still grates on me. ↩︎

In the first year of the new law, any cases you decide are definitionally less than 365 days old. In the long term, the legacy appeals backlog has been cleared, so you have more capacity for the AMA dockets, and you can keep pace so long as the Board is adequately staffed. But in the medium term, even my most optimistic scenarios showed the Board losing the battle to keep pace with its goal unless it worked the Direct Review docket to the exclusion of the others. ↩︎

Board of Veterans’ Appeals, “More Board personnel address pending AMA appeals and wait times.” Retrieved June 9, 2025. ↩︎

- ← Previous

Saying Goodbye - Next →

The Things That Cannot Be Changed